“Salvador Dalí endowed surrealism with a prime instrument of importance, the paranoid-critical method, which he showed himself capable of applying to painting, poetry, movies, the construction of typical surrealist objects, and even fashion, sculpture, art history, and any kind of commentary.”

ANDRE’ BRETON

Salvador Dalí, the renowned surrealist artist, was captivated by the eye. Throughout his prolific career, eyes became a central motif in his works, serving as gateways to realms of imagination, symbolism, and subconscious exploration. Dalí recognized the eye’s power as the conduit for viewers to experience his innermost visions.

For Dalí, the eye was not merely an organ of sight but a tool for revealing the “invisible things”, embodying the theme of the “double image” – where an image suggests or transforms into a second one upon closer observation. His extraordinary creativity was intricately linked with the role of the eye, gaze, and observation, showcasing the ability to construct layered visions beyond initial perceptions.

The iconic “paranoiac-critical method” and the concept of the “double image” might not have emerged without Dalí’s fascination with the eye. He elevated this obsession beyond paintings, incorporating it into sculptures, stage designs, photography, and even his distinctive eyes and mustache, which became emblematic of his visage.

In the realm of cinema, Salvador Dalí harnessed the eye as a tool to depict dreams born from psychoanalysis, achieving striking visual impact and realism. Collaborating with director Alfred Hitchcock in 1945 for the film “Spellbound”, Dalí crafted a series of paintings and drawings, including the monumental piece “Spellbound”, featuring glassy eyes and surrealistic elements, creating an imposing yet magnificent backdrop.

Today, visitors can marvel at the grandeur of “Spellbound” and around fifty other authentic works created by Salvador Dalí at the exhibition “Dalí: Spellbound – The Exhibition” at the Old Philharmonic Hall located in Munich. The exhibition was inaugurated on Friday, February 2nd, 2024, and will remain open until April 2024.

Apart from the exhibition in Munich, numerous artworks in the Dali Universe Collection delve into the theme of the eye, embracing the concept of the “double image.”

In the sculpture “Alice in Wonderland”, the eyes, like the entire face, are concealed by foliage, preceding a floral explosion. Similarly, in the bronze “Saint George and the Dragon”, the absence of facial features underscores the symbolic nature of the figures.

“Profile of Time”, a bronze sculpture conceived by Salvador Dalí in 1977, features a visible open eye, serving as an ode to the “double image” concept. When observed from a specific angle, the sculpture reveals Dalí’s profile, including his nose, mouth, and eye.

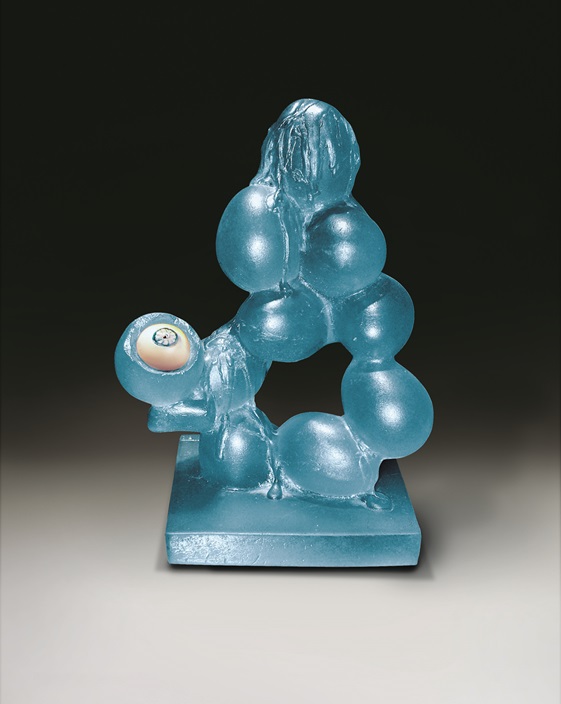

Among the glass sculptures in collaboration with Daum Cristallerie, “Eye of Easter” stands out, echoing Dalí’s obsession with eyes and eggs. This piece, created in 1969, embodies the transparency of the sky and the Mediterranean sea with its cobalt blue hue.

Throughout his life, Salvador Dalí tirelessly studied philosophical, scientific, and religious discoveries, channeling them into his art. With his eyes, he delved into the depths of the unconscious while simultaneously observing the wonders of the cosmos. Dalí once remarked that his entire body of work is a reflection of his thoughts, actions, and now we may add, his vision.

Salvador Dalí’s fascination with the eye transcends mere imagery; it encapsulates his relentless pursuit of understanding and expression. Through his art, he invites us to see beyond the surface, to perceive the world through his kaleidoscopic lens, where every glance reveals a new layer of meaning.

“My work is a reflection, one of the innumerable reflections of what I accomplish, write, think.”

SALVADOR DALI’