“Painting is my least important aspect. The thing that really counts is the almost imperialist structure of my genius. Painting is only an infinitesimal part of that genius”. – Salvador Dalí

Cinema was one of the many domains where Salvador Dalí left his canvas behind to collaborate with legendary filmmakers. To celebrate Dalí’s significant contributions to the world of cinema, it’s essential to start with another genius: Luis Buñuel.

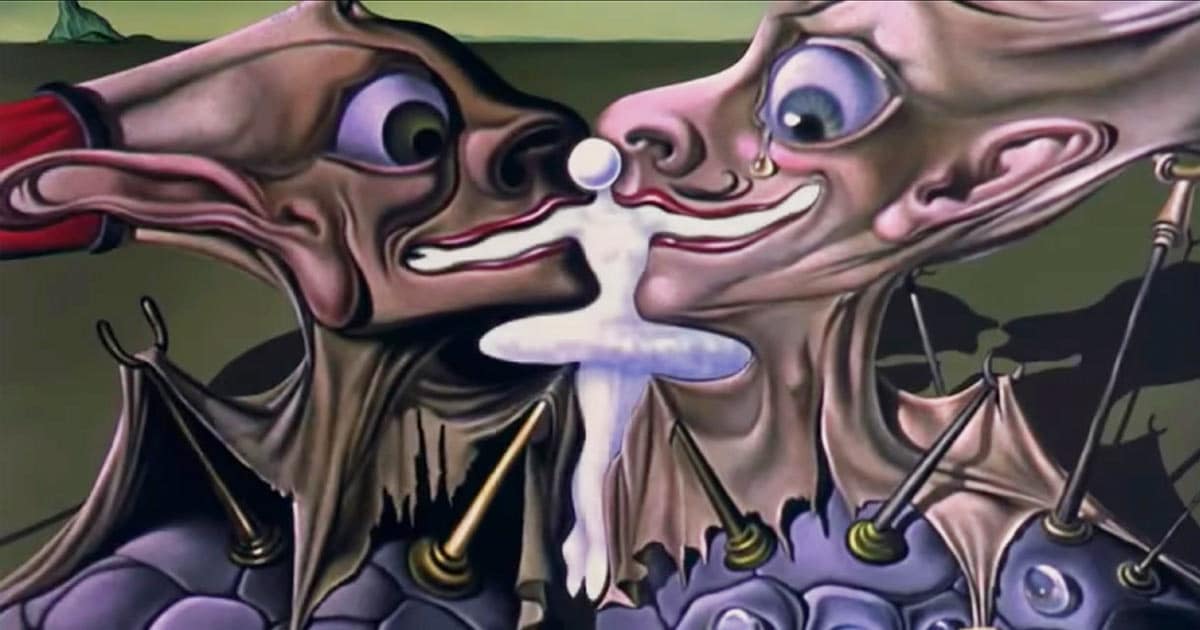

In 1929, the Aragonese director helmed the renowned “Un Chien Andalou”, a short film that has left an indelible mark on the collective imagination. Dalí welcomed Buñuel to his home in Figueres, and during their conversation, the director recounted a vivid dream in which a wispy cloud passed through the moon and a razor sliced across an eye. Dalí, in turn, shared a vision from the previous night of a hand swarming with ants. This surreal exchange laid the groundwork for a collaboration that would influence 20th-century cinema and beyond. This marked Dalí’s first venture into film.

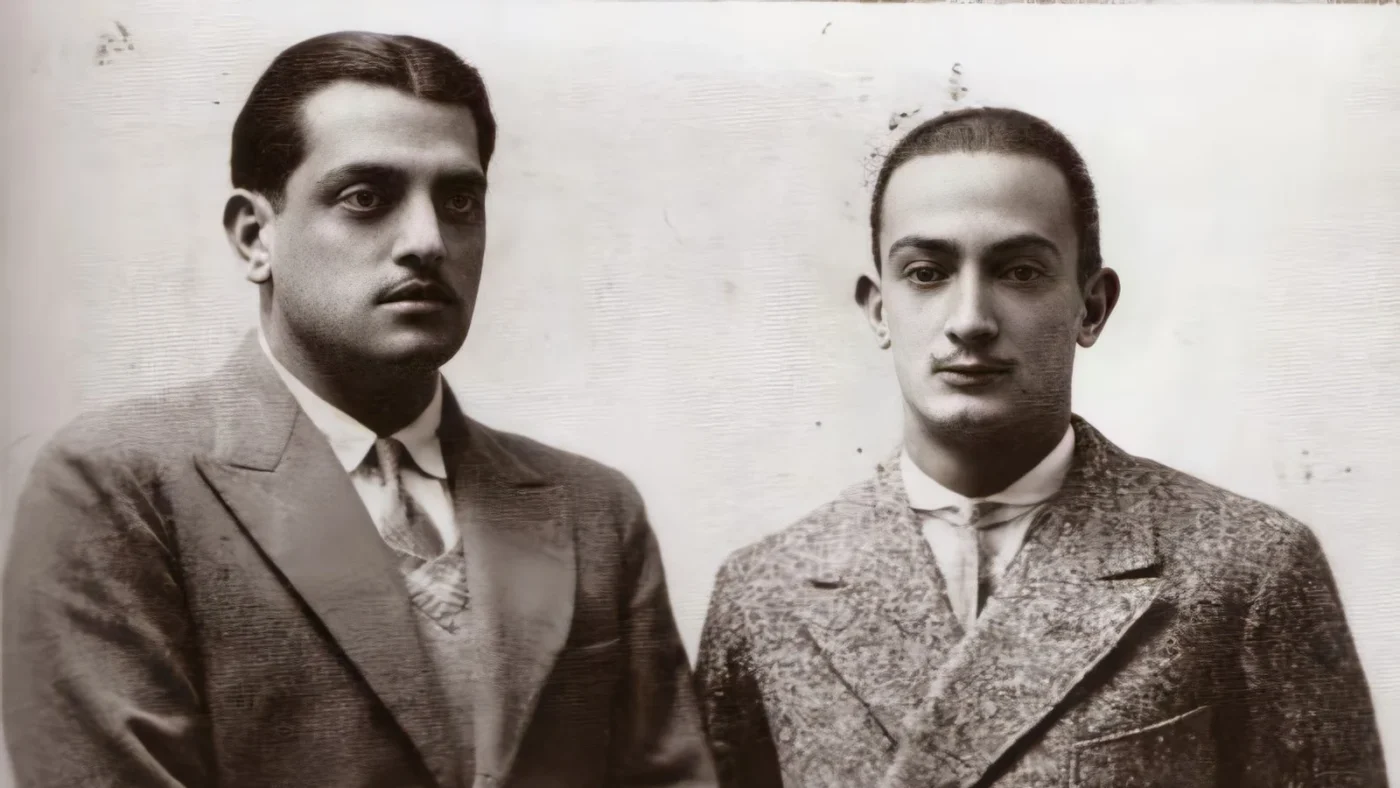

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí. Photo: La Razón

The Spanish writer Eugenio Monter described the film, stating that it establishes “a date in the history of the cinema, a date marked with blood, as Nietzsche liked, as has always been Spain’s way”.

Although directed by Buñuel, the script was co-written by Salvador Dalí, who infused it with dreamlike ideas, such as the now-iconic image of ants crawling over a hand.

Dalí and Buñuel first met at Madrid’s Residencia de Estudiantes, a place that also nurtured figures like Federico García Lorca. The two immediately formed a strong bond, so much so that “Un Chien Andalou” would not be their last collaboration.

The eye-cutting scene in “Un chien andalou“, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, 1928.

Just a year later, they joined forces again for “L’Age d’Or”, an extremely provocative film that offered Buñuel, Dalí, and the rest of the Surrealist Group the freedom to collaborate toward a collective and surreal vision.

Although the script was credited to Buñuel and Dalí, it is rumored that many members of the Group, including Max Ernst, contributed ideas to the project. However, upon completion, Dalí expressed disappointment, stating that “it was a caricature of my ideas”.

Buñuel wasn’t the only filmmaker captivated by the mind of the Master of Surrealism. Another admirer was Alfred Hitchcock. At the height of the psychoanalytic film trend, Hitchcock sought Dalí’s help to design the most famous sequence of “Spellbound”, a film from 1945 starring Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. Hitchcock declared: “I wanted Dalí because of the architectural sharpness of his work”.

“Spellbound”, Salvador Dalí, oil and tempera on canvas, 1945.

The plot, centered around a psychologist’s efforts to unravel the protagonist’s traumas, required a dream sequence filled with scattered eyes, distorted wheels, and vast, surreal spaces. Collaborating with director Alfred Hitchcock, Dalí crafted a series of paintings and drawings, including the monumental piece “Spellbound”, featuring glassy eyes and surreal elements, creating an imposing yet captivating backdrop.

Another Hollywood giant who admired Dalí was Walt Disney. The two became close friends over the years, and Disney wanted the pink elephants sequence in “Dumbo” to be inspired by Dalí’s imagination.

Their collaboration led to the short film “Destino”, which began production in 1946 but was abandoned due to financial issues Disney was facing at the time. However, “Destino” was revived and completed by Disney animators in 2003. The film depicts the tragic fate of Chronos, the Greek god of Time, desperately in love with a mortal, all animated with a Mexican musical background and no dialogue.

“Destino” won an award in 2003 at the International Film Festival in Annecy, France. In 2004, it received an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Short Film and continues to resonate with audiences today. It is a film that unites Dalí’s surrealism with Disney’s unmistakable style.

Each of Dalí’s cinematic endeavors, whether in partnership with Buñuel or collaborating with Hollywood giants like Hitchcock and Walt Disney, was marked by a unique and surrealistic vision that only Salvador Dalí could conceive. For Dalí, true filmmaking was “pure and instinctive, free from the constraints of traditional art”.

The short film “Destino”, Walt Disney and Salvador Dalí, 2003.

In the end, cinema seemed the natural extension of Dalí’s “paranoiac-critical method”, where images coexist, multiply, and consume each other. The armpit hair transforming into a sea urchin in “Un Chien Andalou,” or the shadows multiplying into countless images in “Destino,” mirrored the unhinged surrealism of Harpo Marx, whom Dalí admired.

While Dalí may have struggled to find his place in cinema, cinema found its place in Dalí. His works reflect this symbiosis.

Our exhibition in Modena, Italy, titled “In the Mind of the Master – Salvador Dalí: ‘Art and Psyche’” has a special area dedicated to Dalí and Cinema. Indeed, through his cinematic works, visitors will have the opportunity to delve deeply into the mind of the great Catalan genius and his psyche.

Dali is mainly known for his vast painting production, yet his sculptural work and contributions to Cinema reveal his multifaceted personality along with the key aspects that made him a true genius of Surrealism.

“Painting is my least important aspect. The thing that really counts is the almost imperialist structure of my genius. Painting is only an infinitesimal part of that genius”. – Salvador Dalí